• Energy theft, illegal connections crippling revenue, says Oduntan

• New tariff gaps widen subsidy risks

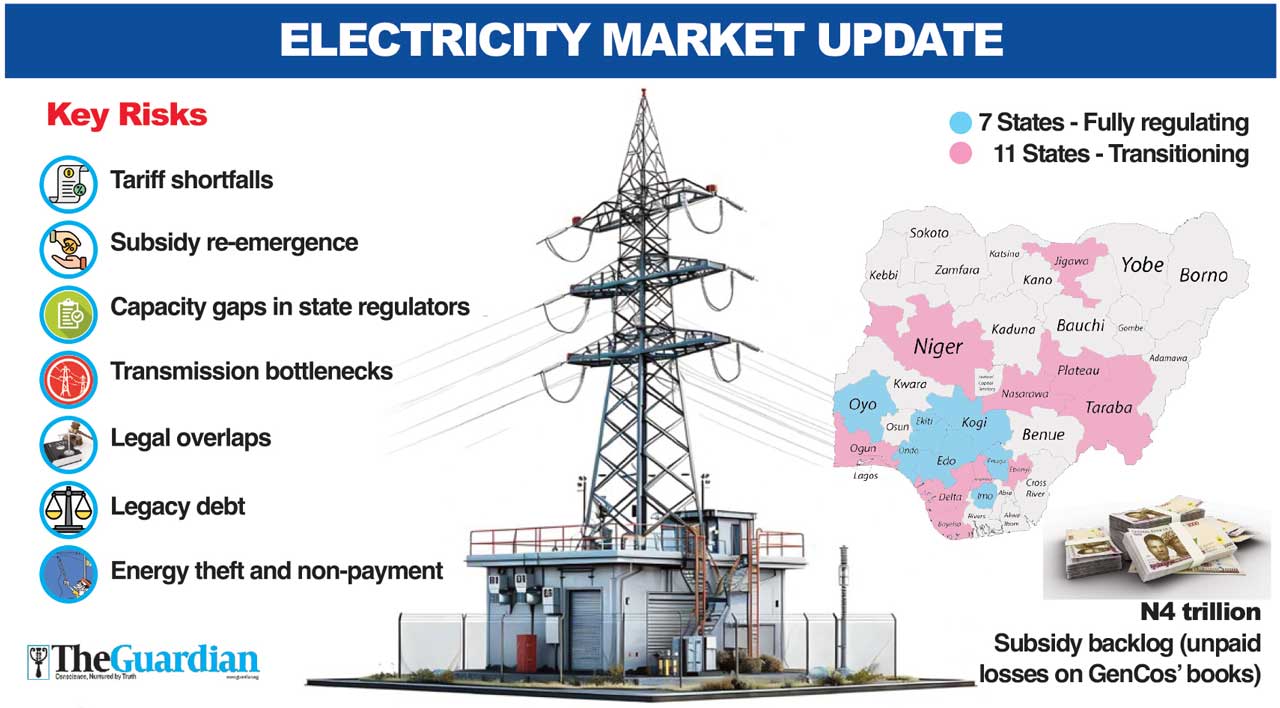

• Experts warn of regulatory conflicts

• FG, partners step in to help states with technical skills

Nigeria’s push for a decentralised electricity market is facing deadlock in 24 states, as tariff structure and debt crisis threaten the contributions of sub-national governments to the distressed sector.

Two years after the signing of the Electricity Act, only about 12 states have been granted regulatory autonomy.

Still, operations of the 12 states, one-third of the sub-nationals, face serious crises as inherent challenges, overlooked in the sector, constrain their operations.

Electricity generation remains at about 4,000 megawatts, with none of the subnational governments able to add any new capacity to the grid.

In the north, more states run to the Rural Electrification Agency (REA) to collaborate on alternative power, thereby weakening the national grid.

Findings show that the high cost of running a cost-reflective market, energy theft, mounting legacy debts and the threat of fresh subsidies have left most states unwilling to embrace the responsibility. For northern states, in particular, the political risk of higher tariffs has proved too steep, reinforcing fears that the Electricity Act may be heading down the path of the same problem it sought to cure.

One notable move under the new law came from the Enugu State Electricity Regulatory Commission (EERC), which issued its first state-level tariff order for MainPower. Band A customers in Enugu now pay N160 per kilowatt-hour, well below the N208/kWh national average.

The EERC’s order assumes an average generation cost of N45/kWh for the next five years, compared to the national wholesale weighted average of N112.6/kWh. The regulator claims lower local costs and reduced operating expenses will shield consumers from steep hikes.

However, experts warn that the gap between actual generation costs and what customers pay could push a fresh subsidy burden back to the Federal Government — re-creating the same distortions the act was meant to fix.

The Guardian gathered that financial constraints and fear of politically-determined tariff structures have slowed real progress across most states.

An electricity market analyst, Lanre Elatuyi, has been a vocal critic of what he calls the over-celebration of the Act. “I have been a major critic of the Electricity Act because some people just woke up and felt that once you give states autonomy, all our power problems will disappear. That is not true,” Elatuyi told The Guardian.

He noted that the Act, which spans over 30 sections, is often reduced in public debate to state-level regulation powers, while other crucial areas like the creation of a national competitive electricity market, a clear Independent System Operator (ISO) and the lingering role of NBET as market administrator remain unclear.

“There’s a struggle because states now have the legal backing to legislate, but they’re still tied to a grid and wholesale market run by federal agencies. That confusion alone has stalled real action,” he said.

Elatuyi argued that the Act borrowed heavily from India’s model without fully adapting it to Nigeria’s context.

“Transmission lines are monopoly networks; you can’t duplicate them easily. We’re only generating about 4,500MW. Who will invest billions in new lines with no supply to the wheel? We borrowed a lot from India’s market design but did not adapt it fully. Now we have parts of the Act clashing with reality on the ground,” he said.

He added that most states lack the manpower and expertise to run an independent electricity market, pointing out that even NERC, the national regulator, still struggles with enforcement. “NERC has been here for over a decade and still struggles. Do we expect states that just got autonomy to build that capacity overnight?” he asked.

He also questioned the assumptions behind Enugu’s lower tariffs.

“They say it’s cost-reflective, but critical costs, legacy debts, CBN loans, and metering funds are ignored. So, if the shortfall isn’t funded, it falls back on the Federal government, and we’re back where we started,” he said.

Elatuyi estimates that the country is already carrying a subsidy backlog of over N4 trillion sitting as unpaid losses on power-generating companies’ books.

“States must not repeat old mistakes. If you want local autonomy, you must also take responsibility for true pricing and liquidity,” he added.

For distribution companies tasked with last-mile supply, the shift to state-level regulation presents both opportunities and logistical headaches. Under the Act, once a state claims regulatory control, the DisCo in that area must restructure into a state-level entity.

Executive Director of Research and Advocacy at the Association of Nigerian Electricity Distributors (ANED), Sunday Oduntan, told The Guardian that DisCos are prepared for the transition but warned that the underlying market remains costly and risky.

“The DisCos are aligning properly. We knew it was coming; we’ve done everything to get ready for the market, but people must understand this is an expensive business with huge recovery challenges,” Oduntan said.

He stressed that widespread energy theft, illegal connections and non-payment by customers, including wealthy consumers, continue to drain revenue.

“It is not just the poor; wealthy people also bypass meters, so cost recovery remains a big problem, which is why many states are hesitant to jump in,” he said.

Oduntan noted that states with stronger economies may succeed faster.

It was learnt that several states in the North and Middle Belt have yet to implement frameworks, partly due to the cost of setting up credible regulators and fears of public backlash over higher tariffs.

A senior industry source who asked not to be named said the reluctance of northern states stems from political risk and financial constraints.

“Most northern states want free things. If states must cover true costs, tariffs will go up, but they don’t want the backlash, so they stick with federal subsidies,” the source said.

The Special Adviser on Media to the Minister of Power, Bolaji Tunji, speaking with The Guardian, said the Federal Government is not surprised by the slow pace.

“The act is specific on the scope for the state regulator and the national regulator. It has taken years to build the capacity of the NERC; so we expect states to catch up gradually,” Tunji said.

He added that the Federal Government and development partners are helping states build technical skills and credible frameworks.

“Once a state gets autonomy, the DisCo in that territory must create a state DisCo. But capacity is key. We are also providing support through development partners to the states in terms of capacity building,” he said.

A big question remains over how truly independent state power markets can be when bulk transmission lines are still owned and operated by the Transmission Company of Nigeria (TCN) and the planned Nigerian Independent System Operator (NISO).

Experts, however, warned that legal overlaps and blurred roles could spark conflicts between NERC and state regulators. Without bold steps to close the generation gap, settle legacy debts and enforce cost-reflective pricing, they caution, local reforms risk repeating old mistakes on a smaller scale.

Comments

This site uses User Verification plugin to reduce spam. See how your comment data is processed.