The 36-state model is a creature of military rule. States lack historical grounding and economic autonomy, making them dependent on monthly allocations from Abuja. Their boundaries often divide people rather than fully unite them, producing constant disputes and grievances.

Regions, while stronger than states, also bundle diverse nations together. The old Western Region contained Yoruba, Edo, and Itsekiri; the old Northern Region lumped Hausa, Fulani, Kanuri, Tiv, Nupe, and many others; while the old Eastern Region combined Igbo, Efik, Ibibio, Ijaw, and other distinct peoples. A return to regions may restore administrative coherence, but it does not solve the legitimacy deficit. A true federal solution must be built on the foundation of identity. Nigerians see themselves first as Yoruba, Igbo, Hausa, Ijaw, Tiv — before they see themselves as ‘from Kogi State’ or ‘from North Central.’ A system that ignores this reality will always wobble. The Federation of Nations Model

The Federation of Nations proposes that Nigeria’s federating units should be its indigenous nations, not artificial states. Large nations such as the Yoruba, Igbo, Hausa, Fulani, Ijaw, and Kanuri could stand as primary units. Smaller nations would have the freedom to federate among themselves or voluntarily align with larger neighbors. The principle is choice — no nation forced into a configuration it does not accept.

Nigeria’s borders remain intact. Abuja remains the federal capital. But the governance map inside the country changes: sovereignty flows from the nations upward, not from Abuja downward. A Democratic Process for Federating Nations

For this model to gain legitimacy, the process must be democratic. Each indigenous nation would hold a popular vote on whether to federate as a stand-alone unit or to form a coalition with others. This ensures freedom of choice and transparency. Following these votes, a National Constitutional Conference would be convened to draft a new constitution. Rather than relying on current federal legislators, delegates would be elected directly from the indigenous nations or coalitions that emerge through the referendum process. Their sole mandate would be to draft a federal constitution based on indigenous nations as federating units, to be submitted for approval through a nationwide referendum requiring a simple majority of 50%+ to pass. This structure gives the conference credibility and firmly grounds it in popular will. Representation would follow a hybrid formula: each nation or coalition is guaranteed at least one delegate, additional delegates are allocated by population size, and an upper cap prevents any single nation from dominating. This avoids the bureaucracy of a bicameral system while balancing equality, democracy, and practicality. What Abuja Should Do

A lean and powerful federal government would remain, with powers limited to a narrow core: Defense and national security.

Abuja’s foremost duty is to protect Nigeria’s borders and guarantee the safety of its citizens. This means maintaining a professional military, coordinating intelligence, and mounting joint operations against threats such as terrorism, insurgency, and organized crime. It also entails exclusive jurisdiction over crimes that cross federating units—financial fraud, trafficking, or corruption—through a federal investigative body, ensuring that no indigenous nation is left vulnerable. By providing this collective shield, Abuja creates the stability that allows indigenous nations to govern, develop, and thrive without fear of collapse or invasion.

Related News

Currency and monetary policy.

A single national currency is the glue of economic unity. Abuja must safeguard the naira’s value, manage inflation, and regulate banking through sound monetary policy. With coherent rules on interest rates and coordination with global markets, businesses and households gain predictability. Without Abuja in this role, indigenous nations could drift into currency fragmentation, trade barriers, and chronic instability. Strong central stewardship of money underpins confidence across the federation.

Foreign affairs and treaties.

In global affairs, Nigeria must speak with one voice. Abuja’s role is to represent the collective will of the federation—negotiating treaties, cultivating alliances, and protecting sovereignty abroad. Allowing individual nations to act alone would fracture Nigeria’s influence and weaken its leverage. Centralizing diplomacy ensures that trade agreements, security partnerships, and development assistance benefit all federating nations while amplifying Nigeria’s global standing.

Interstate commerce and infrastructure.

Abuja should guarantee the free flow of goods, services, and people across indigenous nations by maintaining common rules and shared networks. Roads, ports, railways, power grids, and digital systems are lifelines that cannot be left to fragmented efforts. Education, as part of national infrastructure, should also have minimum federal standards to ensure comparability and quality nationwide. Beyond these baselines, indigenous nations would retain authority to design and deliver education that reflects their histories and priorities. In this way, Abuja ensures coherence, while nations preserve diversity and innovation.

Taxation and revenue remittance.

To fund these limited roles, Abuja must rely on a clear and uniform formula for revenue sharing. Indigenous nations would collect and deploy most taxes themselves, but remit an agreed percentage to the center. This prevents fiscal uncertainty, guarantees Abuja’s core functions, and avoids overreach into local economies. Taxation thus becomes a tool of balance: Abuja remains capable but restrained; indigenous nations remain sovereign yet bound together in a functioning whole.

Nothing more. Abuja would no longer control education, land, policing, taxation, or resources. Those powers would rest squarely with the nations.

For political realism and coalition-building, the National Assembly would remain but with redefined roles:

– The Senate reconstituted to represent nations equally, regardless of population.

– The House of Representatives retained on a population basis but restricted to federal matters.

This preserves continuity and symbolic unity, while limiting the legislature’s scope to Abuja’s lean mandate.

Why This Model Matters

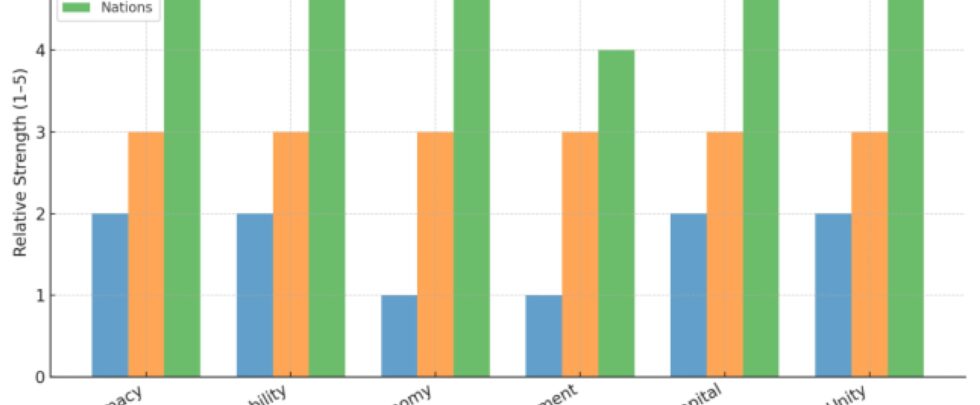

A nationality-led federation offers Nigeria what state- and region-based systems cannot:

– Legitimacy: It aligns governance with identity.

– Accountability: Local leaders could no longer hide behind Abuja.

– Economic autonomy: Resource control returns to the people.

– Conflict management: Internal sovereignty reduces secessionist appeal while recognizing national identity.

– Human capital: Nations tailor education and workforce strategies to their needs.

– Unity through diversity: Nigeria remains one landmass and one sovereign state, but now as a voluntary union of nations.

A Realistic Roadmap

This shift cannot happen overnight. It requires coalition-building and sequencing.

– Short-term (0–2 years): Strengthen local governance through court-backed autonomy for local governments. Decentralize the electricity sector. Begin structured national consultations on federating units based on indigenous nations.

– Medium-term (2–5 years): Ratify a new ‘Federation of Nations’ constitution. Nations establish their fiscal and governance systems. Abuja transitions to its lean core, with royalties and revenue-sharing frameworks agreed upon.

– Long-term (5–10 years): Nations compete and cooperate in education, infrastructure, and innovation. Abuja is confined to its narrow federal mandate. Nigeria matures into a stable union of nations with legitimacy rooted in identity.

The Politics of Reform

Constitutional restructuring is not a purely legal exercise. It is political. Those who benefit from the current system will resist change. Western powers, comfortable with a dysfunctional Nigeria that supplies cheap resources, will not push for reform. Implementation requires building coalitions among nations, civil society, and reform-minded elites.

That is why the Federation of Nations model keeps the Senate and House, even if their scope shrinks. It is a recognition that reform must be realistic to succeed. Sweeping away all institutions at once risks collapse. Retaining them — but redefined — helps smooth the path.

The process of referenda by nations, followed by an elected constitutional conference, ensures legitimacy from below. The hybrid formula for representation balances fairness with practicality, giving both large and small nations confidence in the process.

A Call to Rethink

Nigeria has reached the limits of state-led tinkering. Endless debates about ‘true federalism’ within the current structure will not deliver transformation. What is needed is boldness: a return to the idea of Nigeria as a federation of its nations, not an amalgam of arbitrary states.

Such a system would not erase differences. It would honor them, channel them, and build a union rooted in legitimacy. Nigeria does not need to break apart to achieve stability. It needs to become what it has always been — a country of nations.

Professor Ijose is the CEO of Benin Electricity Distribution Company.