Continued from part 1

Thus, for every Nigerian who made it onto the Forbes list, about 22 million citizens fell deeper into poverty. Is this a mere coincidence? Does it seem reasonable that the creation of a billionaire in the country comes at the expense of over 20 million people sinking into poverty? It can be argued that the poorer the poor become, the richer the rich grow: billionaires, supported by skewed government policies, are amassing wealth at the expense of the impoverished.

Three of these billionaires attribute their fortunes to the oil business, while one credits telecommunications as their primary source of income. Yet, the oil industry is not performing optimally; until recently, over 80% of gasoline consumed in the country was imported, compounded by sporadic supply issues and long queues at local fuel stations. Additionally, internet services remain unreliable, and broad access to broadband is lacking. This raises an important question: how do these billionaires achieve their profits in a system where the market environment is dysfunctional, and the rules appear to be rigged?

This question reminds one of George Stigler’s assertion in “The Theory of Economic Regulation,” which holds that the state possesses a unique resource—the power to coerce—that is not shared with its most powerful citizens. The government uses this power to compel citizens to pay taxes and abide by rules. This coercive authority can be wielded in a way that benefits certain individuals or industries at the expense of others. Businesses often attempt to influence how the state uses its coercive power to “purchase” government products such as subsidies, control over competitive entry, regulation of product substitutes or complements, and price fixing.

It is important to clarify that amassing wealth is not inherently criminal, provided that the rules and policies governing the creation of billionaires are not perverted by government intervention that favours the super-rich. In a fair society, if the economic “pie” grows and the income of the richest increases, the level of inequality should not escalate rapidly. Ideally, billionaires should enrich themselves not through rent-seeking behaviour but by contributing to the expansion of the national economy, enabling the impoverished to escape the clutches of poverty.

One characteristic of the Gilded Age is the decline of public institutions, particularly the education system. The quality of public schools has deteriorated, paving the way for the rise of private universities (with the oldest founded in 1999) and exacerbating inequality in access to high-quality education and earnings.

Prof. Steve Okecha, a prominent critic of the deterioration of the education system and a notable observer of Nigerian tertiary institutions, describes the current situation as “An Ivory Tower with Neither Ivory Nor Tower.” In his latest book, he notes that “beyond the fanciful gates are horrible classrooms; slums called lecture theatres; dry taps, and empty chemistry laboratories.”

This should not come as a surprise to those who have been monitoring education spending in the country. In the aftermath of its peak days, there has been a continuous fall in the government’s investment in education. As a share of GDP, government expenditure on education dropped from over 3% in 1974 to less than 0.5% (0.3%) by 2022.

One significant outcome of a weakened education system is the lack of social mobility. Social mobility has been stagnant in Nigeria for decades, with high-paying jobs typically going to those who possess high-quality degrees. These high-quality degrees depend on a strong foundation of education, which in turn relies on high-quality primary and secondary schools. Unfortunately, students often struggle to obtain a solid educational foundation from Nigerian public schools today. As a result, families must invest in private education to secure these credentials. However, a high-quality private education requires substantial financial resources, creating a barrier for poor families. Consequently, children from affluent households continue to secure well-paid jobs, perpetuating widening inequality in opportunities in Nigeria.

As Nigeria aspires to join the ranks of other great advanced nations, it should consider how these countries operate their educational institutions. For instance, in the United Kingdom, some head teachers in primary schools earn higher salaries than elected officials, such as Members of Parliament (the equivalent of House of Representatives members in Nigeria).

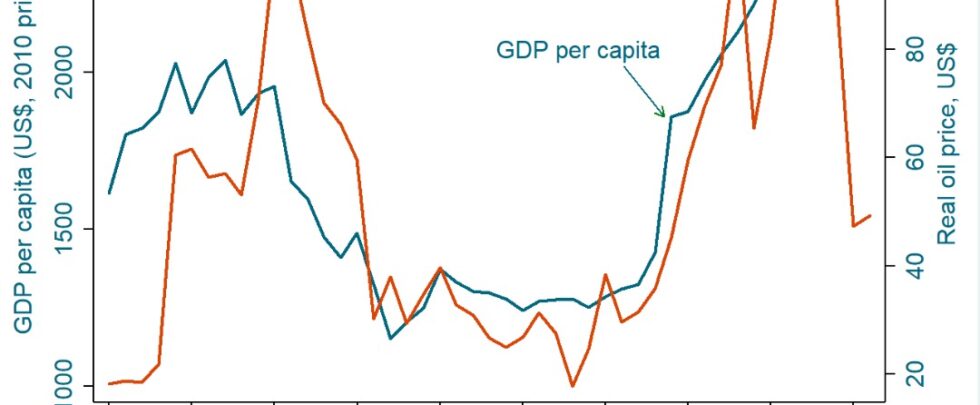

A crucial factor that contributed to the bad economic and social outcomes was the collapse of global oil prices. Since the Nigerian economy has relied heavily on oil revenue for decades, the decline in oil prices has severely affected living standards.

Another indicator of Nigeria’s economic challenges is the inadequate investment in infrastructure and capital formation, which are vital measures of a country’s economic health. Depreciation of the nation’s assets (without replacement) signifies a potentially slower economic growth rate due to limited investment in future production capacity, which hinders long-term growth.

Another indicator of Nigeria’s economic challenges is the inadequate investment in infrastructure and capital formation, which are vital measures of a country’s economic health. Depreciation of the nation’s assets (without replacement) signifies a potentially slower economic growth rate due to limited investment in future production capacity, which hinders long-term growth.

What can we do about the situation?

What can we do about the situation?

Rather than quibble about the past, Nigeria still has the opportunity to depressurise the situation – gather up its pieces, fix the rot in its economic foundation and build a prosperous economy. However, the path to achieving this is an uphill battle that requires a multi-pronged approach focused on economic revival and institutional reawakening. A strong starting point for Nigeria is to work toward self-sufficiency in producing four major categories of goods that Nigerians consume the most: food items, building materials, pharmaceutical products, and clothing/footwear. This initiative should be led by the private sector, with the government playing both a complementary and supplementary role. For industries to function effectively, it is essential to address the energy crisis—power is necessary to energise the private sector, which can, in turn, drive growth and lift millions out of poverty. Moreover, the government must ensure the independence of three key public institutions from the executive branch: the central bank, the national electoral commission, and the judiciary. These institutions are vital for the long-term success of viable economic policies. If the central bank lacks independence, it cannot effectively combat inflation (the primary driver of the economic downturn), nor can it maintain economic stability. Decisions made by the central bank—such as printing or infusing extra cash into the economy (a process known as “quantitative easing), changing exchange rates, or lending money to the government—can be significantly influenced by political pressures. Historically, since 1999, the Central Bank of Nigeria has checked all boxes of a non-independent institution: its governors share the same regional or ethnic background as the president who appoints them, and there has been a frequent turnover in leadership, with four out of five CBN governors never serving their full terms of 10 years. A country cannot progress if its national electoral commission is significantly biased. Election cycles serve as crucial opportunities for ordinary citizens to exercise their right to vote out and replace underperforming leaders. Without this mechanism, ineffective leaders will continue to impose detrimental economic policies on the populace. Unfortunately, this is far from the reality in Nigeria. According to an EU report, between 2007 and 2023, there were a total of 4,982 post-election petitions and appeals filed following the announcement of election results across five general elections. This number indicates a lack of transparency in the electoral process.

Another indicator of Nigeria’s economic challenges is the inadequate investment in infrastructure and capital formation, which are vital measures of a country’s economic health. Depreciation of the nation’s assets (without replacement) signifies a potentially slower economic growth rate due to limited investment in future production capacity, which hinders long-term growth.

Another indicator of Nigeria’s economic challenges is the inadequate investment in infrastructure and capital formation, which are vital measures of a country’s economic health. Depreciation of the nation’s assets (without replacement) signifies a potentially slower economic growth rate due to limited investment in future production capacity, which hinders long-term growth.

What can we do about the situation?

What can we do about the situation?Rather than quibble about the past, Nigeria still has the opportunity to depressurise the situation – gather up its pieces, fix the rot in its economic foundation and build a prosperous economy. However, the path to achieving this is an uphill battle that requires a multi-pronged approach focused on economic revival and institutional reawakening. A strong starting point for Nigeria is to work toward self-sufficiency in producing four major categories of goods that Nigerians consume the most: food items, building materials, pharmaceutical products, and clothing/footwear. This initiative should be led by the private sector, with the government playing both a complementary and supplementary role. For industries to function effectively, it is essential to address the energy crisis—power is necessary to energise the private sector, which can, in turn, drive growth and lift millions out of poverty. Moreover, the government must ensure the independence of three key public institutions from the executive branch: the central bank, the national electoral commission, and the judiciary. These institutions are vital for the long-term success of viable economic policies. If the central bank lacks independence, it cannot effectively combat inflation (the primary driver of the economic downturn), nor can it maintain economic stability. Decisions made by the central bank—such as printing or infusing extra cash into the economy (a process known as “quantitative easing), changing exchange rates, or lending money to the government—can be significantly influenced by political pressures. Historically, since 1999, the Central Bank of Nigeria has checked all boxes of a non-independent institution: its governors share the same regional or ethnic background as the president who appoints them, and there has been a frequent turnover in leadership, with four out of five CBN governors never serving their full terms of 10 years. A country cannot progress if its national electoral commission is significantly biased. Election cycles serve as crucial opportunities for ordinary citizens to exercise their right to vote out and replace underperforming leaders. Without this mechanism, ineffective leaders will continue to impose detrimental economic policies on the populace. Unfortunately, this is far from the reality in Nigeria. According to an EU report, between 2007 and 2023, there were a total of 4,982 post-election petitions and appeals filed following the announcement of election results across five general elections. This number indicates a lack of transparency in the electoral process.

If the ballot box fails as a means of achieving change, the next option for seeking electoral justice is the judiciary. However, if the judiciary is not independent, it may end up validating rather than correcting electoral errors and corruption.