We're in a boom time for reshoring manufacturing—at least to hear our politicians talk about it. President Biden's State of the Union address sounded similar notes to President Trump, with a big focus on "Made in America" and bringing manufacturing back to the U.S.

One of the administration's signature achievements on this front was the CHIPS and Science Act. Signed into law last August, the CHIPS Act represented a significant step forward in expanding and rebuilding semiconductor manufacturing, an industry the U.S. created and dominated for decades.

Yet almost immediately, lobbyists and think tankers started advocating for giving those jobs away to non-Americans. "To unlock the potential of the CHIPS Act, we need a green card cap exemption for STEM immigrants and permitting reform for semiconductor fab construction," proclaimed Alec Stapp, Co-Founder at Institute for Progress. David Shahoulian, a former immigration staffer for Congresswoman Zoe Lofgren and now the head of workforce policy at Intel, agreed. "We are absolutely reliant on being able to hire foreign nationals to fill those needs," he told Politico. And they are hardly the only ones.

— Alec Stapp (@AlecStapp) March 6, 2023To unlock the potential of the CHIPS Act, we need a green card cap exemption for STEM immigrants and permitting reform for semiconductor fab construction.

The current approach is only making it harder to achieve our national security goals.https://t.co/e3OvV9sdJw

These arguments are concerning. Why should the immediate impulse be to give these good-paying jobs away? Especially given that it's simply not true that there are not enough Americans to meet the demands of the blossoming semiconductor industry. Anyone claiming otherwise is failing to account for current STEM workers and the supply of STEM labor projected to come from U.S. universities, as well as ignoring America's past success in meeting semiconductor manufacturing demand.

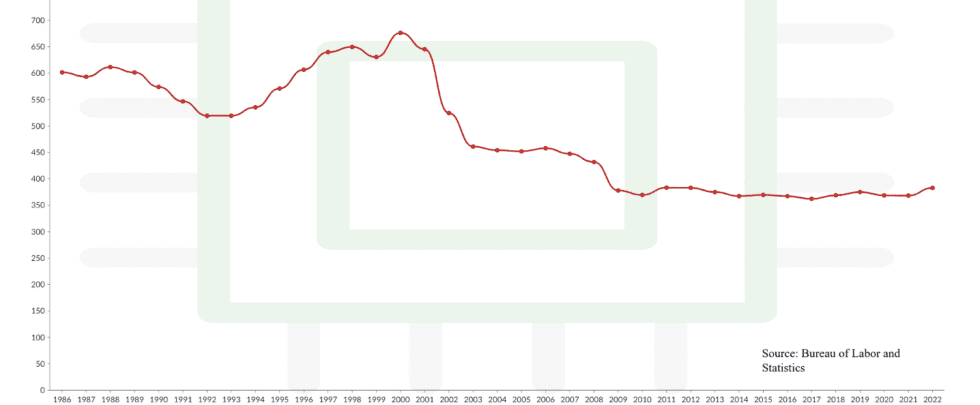

Two decades ago, at its peak, the U.S semiconductor industry employed around 715,000 workers. Today, it employs just 365,000. While semiconductor manufacturing has long been a cyclical industry with booms-and-busts, cyclical booms-and-busts can't explain the sudden and staggering loss of almost 50 percent of U.S. semiconductor jobs.

Where did the jobs go? They moved offshore—for two main reasons. First, competitors in Asia received state support that created an uneven playing field. Second, American semiconductor companies began prioritizing profits over market share and thus shed manufacturing capability. They made a Faustian bargain which may have improved their earnings per share, but productivity and innovation took a hit.

Furthermore, the embrace of the fabless model, a model that contracts manufacturing out to foreign fabrication facilities and instead focusing on the design aspect of semiconductors, drove investment elsewhere.

In other words, the preference for sending jobs abroad and welcoming guest workers to the U.S. ran counter to investing in the existing American workforce.

Many of the jobs sent and created overseas will remain there. But the individuals who formerly held those jobs are still here. Darin Wedel, a former Texas Instruments employee, became the focus of national attention when his wife Jennifer questioned President Obama during an online Q & A. She asked a great question that still bears asking: Why does the government continue to extend H-1B visas when there are tons of Americans like her husband who are qualified?

Obama replied with a non-answer about how engineering is in demand, specifically in high technology areas. Yet when Jennifer Wedel brought up the fact that her husband was a semiconductor engineer, the President had no response.

Overlooking U.S. talent is a sin of omission. But the even more egregious sin is gaslighting Congress into thinking the $52 billion in CHIPS Act subsidies will create a demand for jobs that can only be filled by foreign STEM workers.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

For starters, semiconductor industry employment is estimated to grow by only 13 percent in the next decade, or about 24,000 jobs. That's just 16 percent of the industry jobs created between 1991-2001. Fifty percent of these new jobs will be for engineers and software developers, for which the U.S. already has an existing labor pool—of 1.42 million software developers and 4.4 million trained engineers.

Moreover, in 2019-2020, U.S. colleges awarded over 245,000 bachelor's degrees in computer science and engineering, meaning each new job could be filled two hundred times over by the Class of 2020. Each year, the U.S. has a surplus—not a shortage—of skilled graduates. Keep in mind, only 50 percent of the computer science and engineering students who graduate end up getting hired to work in the industry.

Moreover, 20 percent of these new CHIPS Act jobs will be for lower-skilled technical workers. For the chip factories under construction in Ohio, Intel acknowledges that 70 percent of the 3,000 new fabrication jobs are technical level, meaning they only require an associate's degree.

Again, America has the talent to fill these jobs without relying on foreign workers.

Even supporters of STEM immigration provisions can only realistically justify 3,500 new factory positions needing to be filled by foreign workers. Yet semiconductor industry lobbyists still want a policy that creates an unlimited pipeline of foreign skilled labor.

An unrestricted supply of foreign STEM workers will ultimately hurt American global competitiveness. Top talent is already here. The semiconductor industry's labor shortage is the tech sector's biggest and most repeated myth.

Congress must not fall for it.

Over the pandemic, American semiconductor companies have learned a harsh lesson: They can't outsource and then import their chips in a reliable manner anymore. The same needs to be said for their workers. Pushing shortsighted manufacturing policies and outsourcing labor instead of investing in an American workforce is how the industry got to where it is today.

Kevin Lynn is the founder of U.S. Tech Workers. Lynn writes about the role that the nonimmigrant employment visa system has on skilled white-collar workers. He is based in Pennsylvania. Contact him at klynn @ ifspp dot org.

The views expressed in this article are the writer's own.